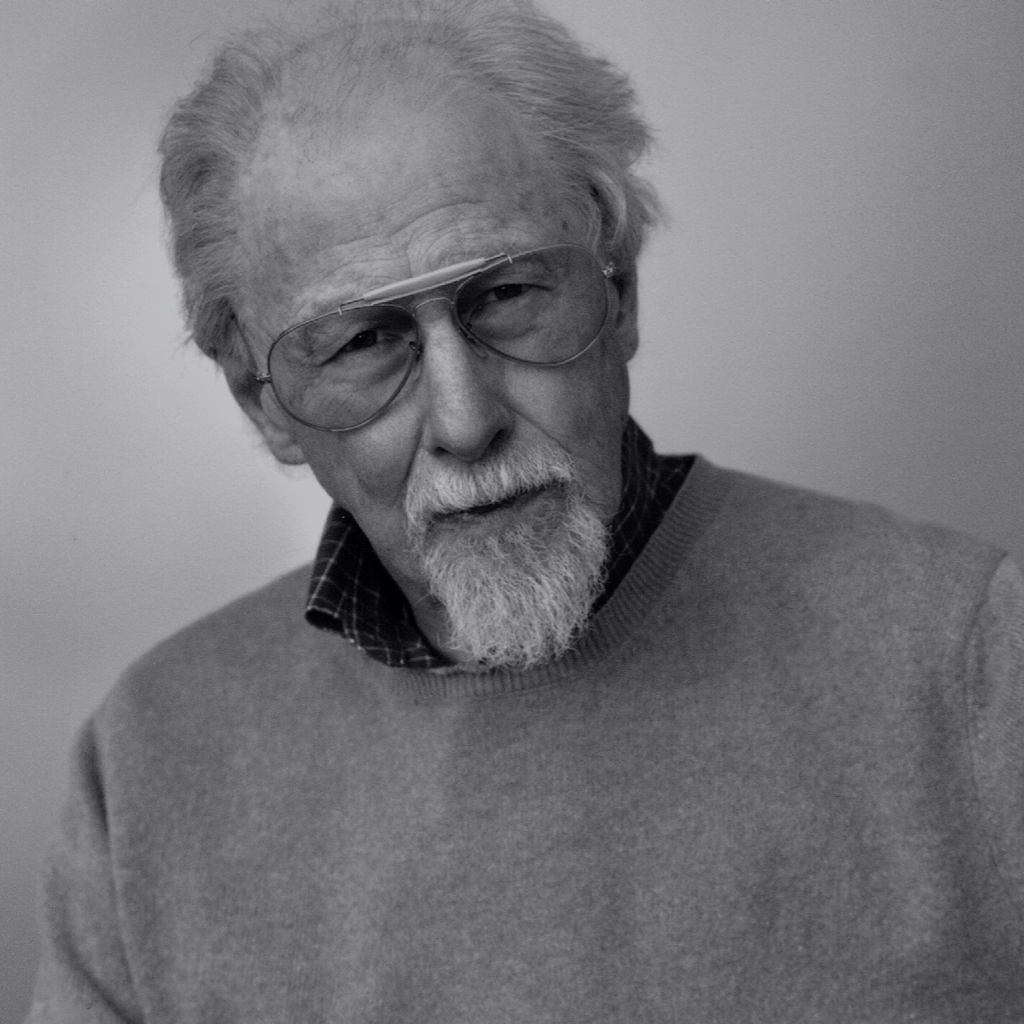

Michael Korda of Simon & Schuster

Looking at life through a thousand sets of eyes.

"FEARLESS CREATIVE LEADERSHIP" PODCAST - TRANSCRIPT

Episode 170: Michael Korda

Hi. I’m Charles Day. I work with creative and innovative companies. I coach and advise their leaders to help them maximize their impact and grow their business. To help them succeed where leadership lives - at the intersection of strategy and humanity.

This week’s guest is Michael Korda, the Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of Simon & Schuster.

We could spend this entire episode talking only about the highlights of Michael’s life. He grew up in 1930s London in a family of movie industry icons. As you’ll hear, he became close friends with Graham Greene, traveled to Budapest to attend the Hungarian Revolution, and joined the RAF. He did all this before he turned 25.

At Simon and Schuster he published books by Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Henry Kissinger, Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Susann, among others. He edited and published all 43 of Mary Higgins Clark’s books, and most, if not all, of Larry McMurtry’s books, including Lonesome Dove.

As a writer, he published over two dozen books of his own, from the autobiographical to the definitive historical accounts of Robert E. Lee and TE Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

He has lived several lives in this one, and helped countless others tell the story of theirs.

He has survived wars, the London Blitz and cancer. And at the end of our conversation, I asked him about the role that fear has played in his extraordinary life.

“I have known people who were without fear, not many, but some, and it's a remarkable phenomenon. My experience is that the important thing is the ability to overcome fear, not to be fearless. Some people are born fearless, but that's often on the borderline of psychosis, as well as being very dangerous. But admitting that you're afraid and overcoming it, is something that we all have to try and do….”

In a world that’s growing more uncertain by the day, living a full and rich life is increasingly challenging. The media fills us with reasons to be afraid. And the debate between trying to stay informed, and trying to get on and live life can fill the mind with a Rubik’s cube of choices.

When you add on top of that, the challenges and risks that come with the responsibility of leading others, then the potential for fear to take over from rational thinking becomes a serious threat.

Fear is a powerful force. In daylight, we are embarrassed by it. At night, we are scarred by it. Rarely do we choose to shine a light on it.

But it is only when we do, only when we admit to ourselves that we are afraid, can we hope to move beyond it. And only then can we help others to join us on the other side.

And then, you can have a life so rich with possibility that it is unimaginable that everything you have experienced could belong to one person.

Here’s Michael Korda.

Charles: (03:08)

Michael, welcome to Fearless, thank you so much for joining me today.

Michael Korda: (03:11)

Not at all, it's my pleasure.

Charles: (03:11)

When did creativity first show up in your life? When were you first conscious of creativity growing up?

Michael Korda: (03:19)

Well, I've never been conscious of creativity not showing up, because my father Vincent Korda was, from 1929 on, a very successful Oscar winning art director and my uncle Alex was a successful motion picture director and producer. And my uncle Zoltan was also a very distinguished motion picture director.

And my mother was a successful actress. And my aunts, Merle Oberon and Joan Gardner, both actresses, Merle being, of course, a movie star of the old fashioned kind. So creativity was all around me and never was something that surprised me. I was not absolutely certain in what form it would come to me, but I never doubted that it would.

Charles: (04:13)

How did you find your own voice in the middle of that rich tapestry of creative expression?

Michael Korda: (04:18)

Well, I think that it's partly luck and partly common sense. I did not necessarily feel - and I have no idea how I arrived at that conclusion - I did not necessarily feel that I was going to go into the motion picture business. That's partly because everybody in my family was already in it. So it seemed hazardous to become a kind of second generation motion picture person.

And partly because my uncle Alex was probably the pre-eminent and most important English motion picture producer and the builder of several big motion picture studios in England, always made it clear that there was not going to be a business to cling to. It would not be a hereditary place in London Films. And of course there was not, because when Alex died in 1956 it all folded up rather rapidly, because it'd been kept going by Alex, kind of balancing act. But when you took him out of the balancing act, the whole thing was not a business that was likely to survive.

So I moved into writing and then took a job in book publishing when I came to New York City in 1957 after participating in the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. I first had a job at Sherry-Lehmann, the wine place, writing the copy for Sherry-Lehmann brands of liquor. And I was quite good at that. But I didn't view that as a permanent career, so I accepted, when it was offered, a job as an assistant at Simon & Schuster to Henry Simon, one of the brothers of the co-founder of Simon & Schuster, Dick Simon, who was the father of Carly Simon. And stepped into book publishing, a job which I'd never, ever considered or thought about or had the faintest desire to become part of.

And to my great good fortune, I found my feet and discovered this is a thing that I can do. I mean I had no idea what an editor does. And yet I discovered that I could do the basic, which is read books. I've always been a great reader all my life. And now somebody was proposing to pay me for it. Not very much, but still something.

And I also discovered that I could edit, which is a whole different matter, and that I was instinctively quite good at it. So it was fortunate. In those days it was possible, because book publishing was less structured and less formally organized, it was possible to get your fingers into everything, even when you weren't directly involved in it. All you had to show was a willingness to read it or have an opinion about it, to write something about it. And you were in the swing of things. And Simon & Schuster was then a very lively place. I wrote a book about it called Another Life - which is actually a pretty good book - it should have been called what I originally wanted to call it, which was Sacred Monsters.

But, I just found, here was something that I could do. I had no particular expectation that it would lead me anywhere and yet it did, basically, so that I was rose high enough to begin to acquire my own books, which is the critical factor in book publishing. But it was not a career I ever intended to follow and I was quite surprised when it worked out for me. I worked at Simon & Schuster for just over 48 years, which is a long time.

And it's really the only serious job I've ever had. I don't know that that's necessarily good career advice to anybody but I do think that there's something to be said, if the company you're working for is one you like, and if you're doing what you like to long term career. I simply felt that Simon & Schuster was in some way a second home for me and it proved to be for almost half a century. That's very lucky and very fortunate.

Charles: (08:59)

I was going to ask you whether you saw yourself as a risk taker growing up?

Michael Korda: (09:03)

Well, I don't know that I was a deliberate risk taker. I lived through part of the Blitz in London in 1940 and that was risky. But of course it was risky in a completely uncontrollable way. Germans dropped bombs, and either they hit you or they didn't, you know? Like a lot of children, because I would then have been seven, I found it very exciting, and it was occasionally very frightening of course. But I think children are as likely to be excited by this kind of thing as they are to be frightened.

And it was very interesting. Then in the winter of 1940, '41, I was transported to Canada, because the British government had decided that, before the war, that London was going to be bombed, on a huge scale. So the Chamberlain government instituted a complicated system of transfer where children were removed at the outbreak of war, to farms and to cities further north in England.

Because the expectation was, in part fueled by a film my father made, of H. G. Wells' Shape Of Things To Come, the expectations that war would begin with a massive bombing of London in which the entire city would be destroyed. And Shape Of Things To Come showed that dramatically, it was a brilliant piece of filmmaking. And it became ingrained in everybody's mind. Of course it didn't happen, the Germans were at that point in no position to bomb London, and they wouldn't be until they conquered France, Holland and Belgium, and had airfields closer to England.

But nobody at the time quite realized it. So it was an enormous disappointment to many people when the expected holocaust failed to rain down on everybody on day one of the war. But, the plans for moving children out of London to safeguard them inexorably went forward because nothing instituted by the civil service is ever delayed. It just grinds on at its own pace. So children, of what were then called the lower classes, were evacuated to farms outside London, and children of the middle classes evacuated to schools and houses in the north of England and children of the rich and influential were shipped over to Canada and from there usually sent to schools in the United States to live with American families. And I was included in that last category.

So in the winter of '40, '41, I was sent on a ship to Quebec with 500 other children. A nightmare voyage. I was the only child on the ship who was never seasick because I don't get seasick, but everybody else was seasick all the time. And it was endlessly long because it was in a convoy that zig-zagged to avoid U-boats. And so I spent most of the war, all of the war in fact, in the United States and came back to England in 1946.

So, there were risks involved, I mean there were several ships full of children that were torpedoed and went down together with all the children, so I suppose that was risky. But on the other hand, I wasn't conscious of taking a risk, if you see what I mean, because it wasn't my decision.

Going to the Hungarian Revolution is something else. I suppose I began to accept risk when I was in the Royal Air Force. I served for two-and-a-half years starting in 1951 and inherently anything to do with flying is risky, so you learn to put up with risk because it's built in to the whole process. Going to the Hungarian Revolution was a special kind of risk because you didn't have to go, and there was every good reason for me not to go since I don't speak Hungarian, I never felt myself particularly Hungarian.

But I think it was in the spirit of having missed out on the Spanish Civil War because my father knew so many people like Bob Capa, the photographer who had been in the Spanish Civil War and he had himself had been in Madrid for some time during the Spanish Civil War. And so this seemed like a chance to play out what had been a very important part of people's lives in the mid to late 1930s. It was of course disappointing because it was short, and also because the good side lost. And also because it was much bloodier and much more frightening than one had supposed.

But I think that kind of thing is probably, if you survived it, good training for the future because you learn to accept that if you don't take risks you're not going to achieve anything. And it's also, although book publishing is based in principle, on making sound choices in terms of which books you're going to publish, both in terms of fiction and non-fiction, it's also intrinsically a gambler's business. Because like the motion picture business, no matter how good it looks, no matter how well it reads, no matter how much you like it, you're still gambling that other people will.

So every book that you buy to publish is a risk like choosing a card at the roulette wheel. Yes, you can apply to it reason, taste, previous experience, all sorts of relatively manageable reasons why a book might or should succeed. But, it's still taking a chance. You're taking a chance of course with somebody else's money rather than your own, but risk taking is an inherent part of all business.

It's very strongly a part of the creative arts. Every show that's produced, whether on television or on the stage, and every motion picture that's produced and every book that's published represents somebody taking a risk based on their own judgment of what matters and what people will want to read or see.

And I think that aspect of the business is a very important one. I've never worked in a business where you do it by percentages and numbers - not mind you that those are any more reliable than anything else. But you feel every time you read a manuscript or hear an idea for a book, you say to yourself, "Well, that could work." But you're taking then a risk. And I would guess over a pretty long lifetime, half a century of publishing books, that certainly more than half of them failed dismally and completely. But that's okay. Dick Snyder, who used to be president of Simon & Schuster for many, many years, was my friend and we were basically a team. And a very fortunate team, because he did the business and the sales and the stuff that doesn't interest me all that much, and I did the books and the editing and the hand-feeding of authors and the stuff that does interest me more.

But, Dick would always say, "If you’re right more than 50% of the time, you're a fucking genius." And of course he's right. In the book publishing industry if you’re right 50% of the time you are a fucking genius. And the same would be true for the theater and the same would certainly be true for television. And the amount of money that's invested in something has no bearing on it. The most expensive projects, as we know, where everything seems right are very often the ones that fail dismally.

So that aspect of risk is part of the excitement and pleasure of working, I think. And in the creative arts it's a component that you can't ignore. If you don't want to take risks then you shouldn't be doing it.

Charles: (17:41)

The art of telling the story has been central to your life. You've helped other people tell their stories, you have told the stories of other people, and you've obviously told your own story. What makes a great story?

Michael Korda: (17:52)

Well the conventional answer to that I suppose is a beginning, a middle and an end. Which is what we always look for in book publishing. And you'd be surprised how many people write long books in which they avoid a beginning, a middle and an end, and the amount of work that has to be done to try and reshape everything so there is a beginning, a middle and an end.

I think that the critical factor for books is that you have to have, in reading the book, a desire to go ahead and read the next page. So that if you're up late at night reading a book, and you don't say to yourself, "Well, it's already midnight but I'm going to read one more chapter," then the book isn't doing its job. Or the writer isn't doing his or her job or the editor isn't doing his or her job. Because ideally, a book should inspire you with the feeling that you need to drop your plans for the rest of the day and read the book. If it does, then it works. If it doesn't, then there's something wrong with it.

Admittedly, tastes are different. No two people like the same kind of book, read the same kind of book, want the same kind of thing out of books. But ultimately, whether it's fiction or nonfiction, it has to propel you along on a conveyor belt of its own and keep you going to the end.

And it has to end with some kind of surprise. Or at any rate, with some kind of resolution. So that you feel that you haven't wasted the time you spent reading the previous 200 or 300 or 400 pages. So any book therefore has to begin with some kind of hook that states what the book is about and why you should be reading it. And it has to keep you reading from page to page. And it has to end in way which makes you put down the book and say, "I'm really glad I read that, and I've learned something," or, "I'm really glad I read that, and I enjoyed the story." If it doesn't, then it's not going to work.

And it is astonishing how many books don't do that. And yet a fair number of people still write, all the time, books that don’t meet that series of criteria and keep people reading. As I said, whether they're non-fiction or whether they're memoirs, whether it's biographies or history, or whether it's a fiction. It's the same thing.

Just as in a play, If there's three acts, the first one has to make you excited to see what's going to happen, and the second one has to be satisfying, and the third act has to end with some kind of surprise and resolution that makes you leave the theater feeling better or exalted, or happy to be alive or something at any rate. And instilling that into the pages of a book is not always easy. But that's the job that it is. And even the most historical of books has the same thing. I would say that for people who enjoy history that reading say, Barbara Tuchman's The Guns Of August is like reading a novel. Even though it's scrupulous history. Even though it's serious stuff, even though the first month of the First World War is a grim subject, I can't pick up The Guns Of August without saying to myself, "Well, I'm just going to have sit down and read this even though I've read it many, many times before."

So the ultimate art of writing is to make people want to read whatever it is to the end. And end with some kind of feeling that they're better off for having read the book. Whether better off emotionally or better off because they've been taught something. Or better off because they just feel better about themselves or about life. But there has to be a payoff for the reader. And getting that into a book is the thing that probably matters the most.

Charles: (22:18)

You've worked with so many different people and so many different writers, so many different authors, have you found there are consistencies in those whose stories are the most interesting to tell?

Michael Korda: (22:30)

It's an interesting question. Some people are just natural storytellers and it doesn't have to do with how well they write necessarily. Because people like Jackie Susann who wrote Valley Of The Dolls, Jeffrey Archer who's written multiple books, are not particularly ‘good’ writers, good, quote-unquote. But have the gift of storytelling down to a T.

And every page, every paragraph wants you to keep going and keep reading. I don't know that it's a personality trait, I think it's a gift that people are born with. I mean, they can learn it, and some people do. But the ones who are really good at it are natural. They're, they're people who in conversation are always telling a story and rounding it out and making it good.

It is a real and powerful gift. But I don't know that it's any particular type of person who is likely to share that gift, if you see what I mean?

Charles: (23:33)

Who are the writers that most surprised you?

Michael Korda: (23:37)

There are people whose imaginative power is such that you're constantly surprised by what they do even though you may not like it and even though it may not always work in terms of selling books. For a period of his career I published Richard Adams who wrote Watership Down, a book I thought was wonderful. And Adams had a wonderfully inventive mind because if you said to somebody, "Well, how would you feel about a 400 page-novel in which all the characters are rabbits except for one who is a seagull,” you'd say, “You've got to be out of your mind.”

But Richard Adams somehow, out of nowhere, produced this massive international bestseller. Huge, huge, huge novel, all the characters of which were rabbits. And his mind constantly worked in that way, so he wrote, for example, a wonderful book - he was English, but he got interested in the American Civil War - and wrote a novel about the American Civil War as seen through the eyes of Robert E. Lee's horse, Traveller, who is telling his story of the Civil War to the stable cat, towards the end of his life.

Now, the fact of the matter is, I've been a relatively successful - with some complete failures and duds - writer for 23 or 24 books. But I cannot imagine the circumstances under which I would say, "I've got a good idea, why don't I write the story of the American Civil War as seen through the eyes of Robert E. Lee's horse talking to the stable cat?" So, there's a degree of imaginative power which I don't have. Or at any rate, I don't have it to that degree.

And that's actually the most interesting thing about writing and about book publishing is that ability to come up with ideas that sound totally implausible but yet which you make to work. And I guess that's in the end the thing which interests me most about book publishing, although I'm now out of it - my last three remaining authors stopped writing. Well, two of them are dead. Mary Higgins Clark died a few years ago. Larry McMurtry died a year or more ago. And Henry Kissinger is of course still alive and well, but I haven't seen any pages from him recently.

But, the possibility that the next manuscript on your desk will be that kind of surprise is really the thing that keeps you going in book publishing. I mean the rest of it would be easy if you just said, or were able to say, "Well, spy stories are selling, so let's buy a few spy novels." I mean, that's not going to produce John le Carre necessarily but it's at any rate an approach to publishing which might get you a certain number of books, if you pick up the phone and call agents and say, "I'm looking for spy novels." You'll pretty soon have an office full of spy manuscripts.

But finding something that's a totally different and new way of looking at the world and putting it into a book, is a whole other business. Not every editor's necessarily attuned to finding that.

But to my mind, the ultimate pleasure of book publishing is to find something so unexpected and new, that you'd never really imagined it could exist. That's not going to happen often, by the way. I think if it happens only a few times in an editor's career, it's a lot. But when it does happen it's terrific. And it is the greatest feeling when you read something and say, "Wow, I absolutely had no idea that anybody would do this, and it really is wonderful." That compensates for a lot of otherwise dreary reading in publishing.

Charles: (27:53)

What did you learn about giving feedback? You obviously worked with so many different kinds of people, so many different personalities, so many different walks of life. What did you learn about how to give feedback that people could hear?

Michael Korda: (28:05)

Well, of course every editor is different. I have always tried to couch criticism in editing with a thin layer of praise, which simply makes it easier to swallow. It's like the sugar coating on a pill. Sometimes you just can't do that and you've got to say, "Look, this doesn't fucking work. You've got to go back to the old drawing board and rethink it.”

I think that that's a portion of editing that's very important. And I think generally in the creative arts very important, is to be able to convey enthusiasm and support, and a positive outlook. Somebody once said theatrical producers, I can't remember who it was, it may have been Moss Hart in Act One that said that a producer's a man who comes into the rehearsal on the first day, and says, "I don't like the shoes."

But the truth of the matter is that producers succeed because they're able to convey an enthusiasm, a degree of support. They admire talent and are not threatened by it. Which is a very important thing. And they're able to get what they want out of difficult people, which actors and actresses are likely to be if they're any good.

And some combination of those things, together with an enormous helping of curiosity, are the things that are necessary for anybody in the creative arts.

Charles: (29:46)

What's your process for writing? When you are struck by a thought or an idea or a subject of interest. How do you go about beginning your process?

Michael Korda: (29:59)

Well, I think the first thing is you have to have the ability to sit down and actually translate your thoughts and your objective into words on the page. Because you can sit all day thinking about things, and may have very interesting thoughts, but until the words go down on the page they haven't gone anywhere, if you see what I mean. So the first is the ability to sit down and actually start writing or typing.

The second, and that's much harder to describe, that you have to like what you're writing. If you don't think it's any good, then nobody else will. And if you don't think what you're writing about is interesting, then very few other people are likely to find it interesting. So, you have to get interested in the subject. Interested enough to carry you through the amount of time it takes, in my case, to write a book, which can be considerable. When I wrote Clouds Of Glory, my biography of Robert E. Lee, the American Civil War - I knew a great deal about it and had read a lot about it over the years.

But still, it's a big chunk of history and it took me between three and four years to write the book. You've got to be interested in Robert E. Lee to last three or four years. and the same is true for Hero, my biography of T. E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia. That took almost four years.

So, a passing interest in a subject is not going to get you through a book. It has to be something that makes you feel every day, yes I want to read more about him or her. I need to know more about this, I'm interested in that. And if you don't feel that, the book is almost certainly not going to interest anybody else.

Charles: (31:49)

Do you have a daily routine when you're writing a book? Are you committed to, “I want to produce something every day?”

Michael Korda: (31:54)

Well, the entire world is pretty much committed to disrupting my daily routine. So the answer to that question is I try to create a daily routine for myself every day, but I'm not inflexible about it. I mean, it's the whole Proust cork-lined room in which you lock yourself for several hours of every day to write. I don't do that. I probably should, I wish I had. I wish I could. But I don't do that.

But I do say to myself, for example, if we're having this conversation this morning, I'll say to myself, "Well, I need to set aside a couple of hours this afternoon to write." I’m fortunate that I never made my living entirely by writing. I've always been a book publisher and book editor, and that's been my chief profession. If all I did for a living was to write, then I might have to construct a more disciplined world in which to live. No question about that.

But I'm pretty disciplined. Once I sit down, I tend to keep going. My mind recovers from interruptions, many people do not. I'm capable of stopping doing something ordinary, answering the telephone, reading an article in the New Yorker, and then getting back to what I'm doing. Not everybody can do that.

As I say, I'm not sure that there's any one way in which people write or work well. There really isn't. Everybody contrives their own solution. Graham Greene, who was an author of mine but also a very close friend of mine, from my teenage years onto his death, wrote 500 words every day. But exactly 500 words, by some counting system of his own. Because he would write 500 words even if it meant stopping in the middle of a sentence. With a fountain pen with a very fine nib and a tiny little black notebook that he bought quantities of from that expensive English stationery shop on Curzon Street and I can't remember what it's called anymore.

And every morning Graham would get up very early in the morning, no matter how exciting his night had been before, and write exactly 500 words in minuscule, almost invisible handwriting. And on the 500th word he would close it up and put it in his pocket and screw the top on his fountain pen and say, "Right, let's get on with life." And not think about it for the rest of the day.

I'm not sure that that system would work for me or for anyone else, come to that, but it certainly worked for Graham Greene.

Charles: (34:43)

And he wrote all of his books that way?

Michael Korda: (34:44)

Yeah, all of his work, absolutely. A lot of books. So everybody finds their own method, and whatever it is, it's a highly personal thing.

Charles: (34:54)

So on those days when you were both editing and writing, you were able to flip back and forth in terms of the mindset? The differences that those required?

Michael Korda: (35:00)

Yes, I've always thought of them as completely unrelated and different jobs. so that's been a help, yes. And obviously some days there wasn't time for me to write. But I would try and put aside the time for both, I'm not sure I could do that anymore. I mean, when I was starting out writing, I used to get up at 5:00 in the morning and write ‘til 7:00 or 7:30 and then go to the office. I haven't done that for years. But I did do it for a whole number of years. And it worked.

If you really want to do it, you find the time for it, is my experience.

Charles: (35:34)

You obviously edited a great many very successful books, and this you mentioned a couple of times there were some that didn't work. As you look back at the ones that didn't work, could you see themes or reasons why they hadn't worked?

Michael Korda: (35:46)

Well, often it's because they were just basically at heart lousy. A lot of it comes, first of all, from a grotesque amount of self-confidence and optimism. In that, you suppose that you can make it work, that you say, "Well, this really isn't much good, but once I get to work and really edit it, it's going to be terrific." And that's often not true.

Some of it is just plain mistakes. People will love this book and yet everybody who reads it says, "Nah, I don't see what's so special about this." It’s also easy to become interested in something and conclude that everybody else will be interested in it.

Now you know, stuff can be bizarre, I had a huge success with a book that taught you how to make paper airplanes and was quite a large format book. And the paper airplanes were there in the book, so you could tear out a page and it showed you exactly where to fold it and how to fold it and where to cut and you made these elaborate paper airplanes. And I thought that that was pretty interesting. Nobody at Simon & Schuster was even remotely interested. But I went ahead with it anyway and it was a very complicated production job and the book was a humongous bestseller. Amazing.

But it could just as easily have folded flat. The fact that you're interested in something does not necessarily mean that other people will be. And you could only gauge that up to a certain point. I think actually it's that kind of chance is what's really interesting about book publishing, is the rare opportunity when something comes along that you find interesting and fascinating that other people will also find interesting and fascinating.

You could say to yourself, "How many people are going to read a book by an Englishman about spending a year in Provence?" But Peter Mayle's A Year In Provence was a humongous worldwide bestseller.

Partly because it was a wonderfully written book, but also because people found the whole notion of a year in Provence and buying a house and dealing with the French, they found it utterly fascinating. They could just as easily have not found it fascinating, if you see what I mean?

And also, derivative publishing is almost certain to fail. If you say to yourself, “A Year In Provence worked, why don't we get somebody to do that about Maine?" Well, no.

You know? It worked because that's what it was. It was about Provence and people were interested and they liked it. You can't simply repeat that and apply it to other things necessarily. And so I think that's important. Almost all things that are imitative fail.

Charles: (38:42)

You talked a little bit about the self-confidence that you have to have, to believe that you can make something work and almost the hubris that goes with that. Obviously that kind of confidence is critical to original expression, without the willingness to try and the willingness to fail, it's hard to imagine original expression ever coming to light. What did you learn about holding that for yourself even when something hadn't worked? How did you hold onto that sense of confidence for the next time?

Michael Korda: (39:11)

It's a lot like gambling. People gamble not necessarily because they've won, but because they believe that they will win even after they fail. Otherwise they would only sit down at the table once and then get up and walk away. And the same is true for book publishing. People who really love the whole idea and are inspired and interested in it, are going accept a certain amount of being wrong and having failures.

I think you really have to be able to do that. I mean, you're not going to learn how to do anything unless you fail at it several times. And then strive to overcome that. Obviously, the mere fact of wanting to dance like Fred Astaire isn’t going to make you dance like Fred Astaire. But if you're going to learn to dance, then you're going to have to accept a lot of times when you fall, when you slip, when you don't get it right until eventually you do get it right.

And I think that that's probably the most important thing, is not to become downhearted when things don't work. but to say to yourself, "Okay, it didn't work, I'll get it on, and do it again.” But do it differently and better next time. I think that's an important part of life. If you can't do that, you're not going to get anywhere.

Charles: (40:30)

As you look at your career so far, what gives you the most satisfaction? Or the most pleasure?

Michael Korda: (40:39)

I'm very happy with certain books I've published over the years, and with certain relationships I've had with authors over the years. The one with Mary Higgins Clark was striking because I believe that I was Mary's editor for all 43 of the books that she wrote. Now, admittedly, none of Mary's books was War And Peace, but she was a very artful and good storyteller, hugely successful. Sold millions of copies in every possible language. Wrote a book a year, or even two books a year, and so that was a very big part of my life.

I was Larry McMurtry's editor virtually during his whole writing career and I would say that if I had to pick the books that I'm proudest of publishing, I would put Lonesome Dove right up there as one of the moments in my career that gave me the most satisfaction. Because that was a book that I loved and a novel that I thought was absolutely wonderful. And I never found anybody who didn't like it. Everybody liked Lonesome Dove.

But for years Larry ground out wonderful novels which never sold many copies but had an enthusiastic audience within Texas. I used to say at every Simon & Schuster sales conference when I was presenting a Larry McMurtry novel, I would say, “One of these days, I promise you, Larry McMurtry is going to write the Moby Dick of the American West." When he wrote a big novel about rodeo, called, Moving On. And when I say big, it was huge, 800 or 900 pages, I said, "It's the Moby Dick of rodeo."

It didn't work, it turned out that that there were fewer people interested in rodeo than I thought.

Or anyway, the people who were interested in rodeo weren't interested in reading novels. And so it rather fizzled. Then at some point the enormous manuscript for Lonesome Dove came in, because that was huge. And I remember carrying it onto the stage when I presented the book to the Simon & Schuster sales representatives and saying, "Okay, I've been promising this for year, but here it is. It's the Moby Dick of the American Plains at last.” And it was. So that was a great moment in my career.

I was very proud to publish Henry Kissinger's Diplomacy, because I thought it was a brilliant and serious and wonderfully done book. I was very proud to publish Richard Rhodes, The Making Of The Atomic Bomb, because I thought it was an important book. It won the Pulitzer Prize.

That's three books which mean a lot to me. There are probably dozens of others that mean a lot to me which I haven't thought of. But those three were important. Both in terms of my career, but much more important in terms of my own satisfaction in publishing a book.

Charles: (43:38)

You've lived through wars, you've lived in peace, you've lived in different countries. You've lived through different eras. As you look back at your life, what role do you think fear has played in it?

Michael Korda: (43:49)

I think fear is an enormously negative emotion. I have known people who were without fear, not many, but some, and it's a remarkable phenomenon. My experience is that the important thing is the ability to overcome fear, not to be fearless. Some people are born fearless, but that's often on the borderline of psychosis, as well as being very dangerous.

But admitting that you're afraid and overcoming it, is something that we all have to try and do and I think that's the important thing. So I try just to overcome... I don't say to myself, "I'm not afraid of this." I mean, at this point in my life there all sorts of things I could be afraid of. But practically speaking, I'm not at Kabul airport trying to get on an airplane. So I mean it's not that kind of fear. I've experienced that, certainly in 1940 and much more profoundly in 1956 during the Hungarian Revolution.

But the point is not to be without fear but to overcome the fear. That's what matters. And I think that's the case with most people. There are very few people who are totally fearless. And even the ones who are totally fearless usually turn out to be fearful of something. So, I think all of us have a certain quota of fear that's built into us.

Charles: (45:16)

I want to thank you so much for joining me today and letting me into your life a little bit.

Michael Korda: (45:20)

Oh, you're very, very welcome. I've enjoyed it myself. I would like to think that it's useful to somebody. It's a natural thing when you reach, as I am, close to the age of 88, to suppose that what you know will be useful to other people. Ralph Richardson, the great English actor whom I knew very well and was very fond of, I dearly loved Ralph. Ralph said, "I thought that when I grew old, I'd be jolly wise and people would come to me for good advice. But now I'm old, nobody comes to see me at all, and I don't know a bloody thing." And I think that pretty well sums up my feeling about myself. Nobody comes to seek my advice and I don't know a bloody thing. I didn't appreciate it until I reached this age, but now I understand completely what Ralph was saying.

Charles: (46:20)

Well, I think it is their loss if they do not, and I am grateful to you for sharing today. So thank you so much for joining me.

Michael Korda: (46:26)

I thank you.

—————

Let us know if there are other guests you’d like to hear from, and areas you’d like to know more about or questions you have.

And don’t forget to share Fearless with your friends and colleagues.

If you’d like more, go to fearlesscreativeleadership.com where you’ll find the audio and the transcripts of every episode.

If you’d like to know more about our leadership practice, go to thelookinglass.com.

Fearless is produced by Podfly. Frances Harlow is the show’s Executive Producer. Josh Suhy is our Producer and editor. Sarah Pardoe is the Media Director for Fearless.

Thanks for listening.